After more than a year of community discussions and considerations, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced in February 2019 its intention to regulate two drinking water contaminants, aiming to address a growing national public health issue. If the EPA follows through, this would mark the first time in almost two decades that it has established an enforceable standard for a new chemical contaminant under the Safe Drinking Water Act. These contaminants, PFOA and PFOS, have polluted water supplies across the nation, impacting millions of Americans. They are part of a group of man-made chemicals known as PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, utilized in products like firefighting foams, waterproof clothing, stain-resistant furniture, food packaging, and dental floss. These substances have been associated with several health issues, such as cancers, thyroid disease, high cholesterol, low birth weights, and immune system effects.

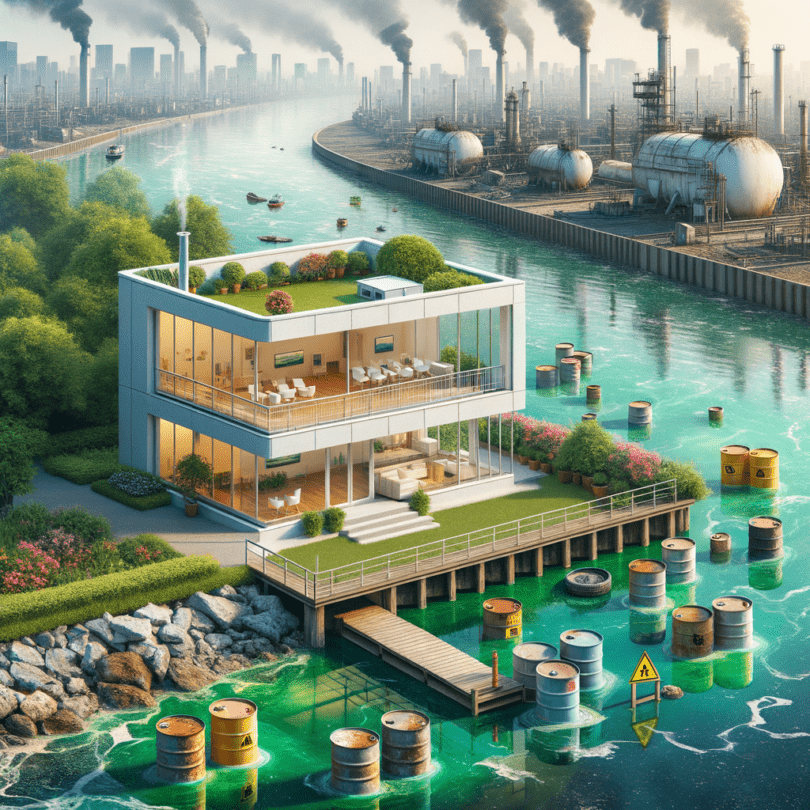

Research indicates that PFAS exposure in children might reduce vaccine effectiveness—a subject my colleagues and I are currently studying in a project called PFAS-REACH. Laboratory research has shown that even low levels of PFAS can affect mammary gland development, potentially increasing breast cancer risk later in life. Additionally, PFAS are extremely durable, not breaking down once released into the environment, which is why they are often referred to as “forever chemicals.” Although PFAS have been utilized for decades, only recently have we begun to understand the extent of the contamination. A 2016 study revealed that more than 16 million Americans are exposed to these toxins in their water, with a recent estimate raising that number to 110 million. PFAS enter water supplies from places like military fire training sites, airports, industrial locations, and wastewater treatment facilities. In 2010, my colleagues and I at the Silent Spring Institute, focused on the relationship between environmental chemicals and women’s health, first detected PFAS in water wells on Cape Cod, Massachusetts.

The Department of Defense has identified around 400 military sites with known or suspected contamination, mainly from firefighting foam usage. Presently, there are over 4,700 PFAS substances being used. All share similar chemical properties and persistence. While the U.S. stopped using PFOS in products by 2000 and PFOA by 2006, they still widely appear in drinking water, necessitating state demands for FDA guideline levels of safe exposure. Current studies indicate that some newer PFAS have comparable health impacts, and most have not been researched yet. Scientists are diligently working to understand these substances better to reduce public exposure. For instance, researchers in the STEEP Superfund Program, which I am involved with, are examining these chemicals’ environmental movement, chemical traits, accumulation in human bodies, and health impacts. Since 2009, the EPA has considered regulating PFOS and PFOA in drinking water.

The agency’s recent decision is a positive step, but it only targets these two chemicals, with any new federal standards not fully applying for years. Earlier this year, my colleagues and I analyzed differences in state and federal regulatory approaches to these contaminants in drinking water. We found seven states have their own guideline levels for PFOA and PFOS; some, like Vermont, Minnesota, and New Jersey, enforce stricter levels than the current non-enforceable EPA guidelines. More recently, New Hampshire, New York, and California proposed guideline levels lower than the EPA’s. The day after the EPA’s announcement, Pennsylvania plans to create its guidelines, citing concerns about the EPA’s pace in addressing the issue.

Meanwhile, some states are crafting additional guidelines for other PFAS chemicals. Minnesota’s guidelines include PFBS, a chemical used in Scotchgard. North Carolina is focusing on GenX, a substitute detected in their local water, air, and soil. A key question is how the EPA’s drinking water standards for PFOA and PFOS will compare to state efforts. Will the agency consider comprehensive scientific evidence on the health risks of these chemicals when setting a “safe” drinking water limit? Will impacts on sensitive groups, like pregnant women and children, be included? Although the science is still developing, one thing is evident: More is known about these chemicals, revealing health effects at increasingly lower levels. It’s crucial to allow states the flexibility to enforce stricter measures than the EPA’s, as there is much to learn from states’ guidelines.

However, the growing regulatory patchwork is concerning, as some Americans might not be sufficiently protected. Some states have the means and expertise to conduct risk assessments, but others may lack the funding and knowledge. Political and social influences, as well as industry pressures, can lead to unequal exposure, with some communities safeguarded and others at risk. A federal standard could ensure uniform protection for everyone, irrespective of state capabilities. The EPA’s plan includes other promising measures, like declaring PFOS and PFOA as “hazardous substances” under the Superfund law to assign contamination liability and support cleanup efforts, enhance drinking water monitoring, and improve industry release reporting. However, the plan primarily focuses on existing contaminated sites, not preventing these chemicals from entering water supplies and the environment.

Assessing the risk for individual PFAS compounds separately is inefficient. Many advocacy groups and scientists—including colleagues at the Green Science Policy Institute—are advocating for class-based regulation of these chemicals. Under the Toxic Substances Control Act, the EPA can limit new toxic chemicals’ approval. However, new chemicals often receive approval without thorough assessments. Considering concerns about PFAS compounds’ persistence and mobility, I believe restricting this entire class of chemicals is sensible. There are precedents for similar actions. In 1979, the United States banned PCBs after these persistent and toxic chemicals spread widely in the environment. The global community banned chlorofluorocarbons in 1996 when scientists found they harm the ozone layer. In 2017, the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission voted to prohibit an entire class of toxic flame retardants from consumer products.